The Last Chopper Out of Nam

What our continued political division means for the future of women, men and our ability to relate to one another.

Hello and welcome to Many Such Cases.

Even prior to yesterday afternoon, I felt as though all I saw when I opened my phone was horror, division, anxiety, and hatred. And then, Charlie Kirk was killed.

I wasn't really sure how much about this I wanted to say myself. I was no fan of Charlie Kirk. Still, it is my personal belief — an aspect of my spiritual foundation, I suppose — that I think all people are worthy of our redemption and prayer for hope and change. To me, much of what Kirk espoused was corrosive to the soul, but so too is celebrating his death. All around, we’re bombarded with toxicity in large part because a set of tech companies have ran the numbers and found that it keeps us online longer.

This is not, obviously, the first time that somebody has been killed for their political beliefs in a public manner. It won't be the last, either. But what I do think separates this particular death and also speaks to the broader cultural environment that we have existed in over the last several years is how oversaturated it can feel, how exposed we are to the division of it all. It feels as though we are being pushed to divide and separate at every moment, not just online but within our own personal lives.

I’ve mentioned the repetition of the phrase “catching the last chopper out of ‘Nam,” and how it has come to represent what many see as the romantic future of young people. That is ultimately the only context I hear it used these days. Those of us lucky enough to have found love, to be in steady and committed relationships (especially ones formed separate from dating apps) are considered to have escaped something. We got out of all this — the gendered hostility, the suspicion, the surveillance, the loneliness — by the seat of our pants. And while I’ve found the sentiment that the phrase reflects useful in assessing our current attitude towards sex and relationships, it suggests a pessimism by which I don’t abide. This can’t be it, right? Surely it doesn’t end here.

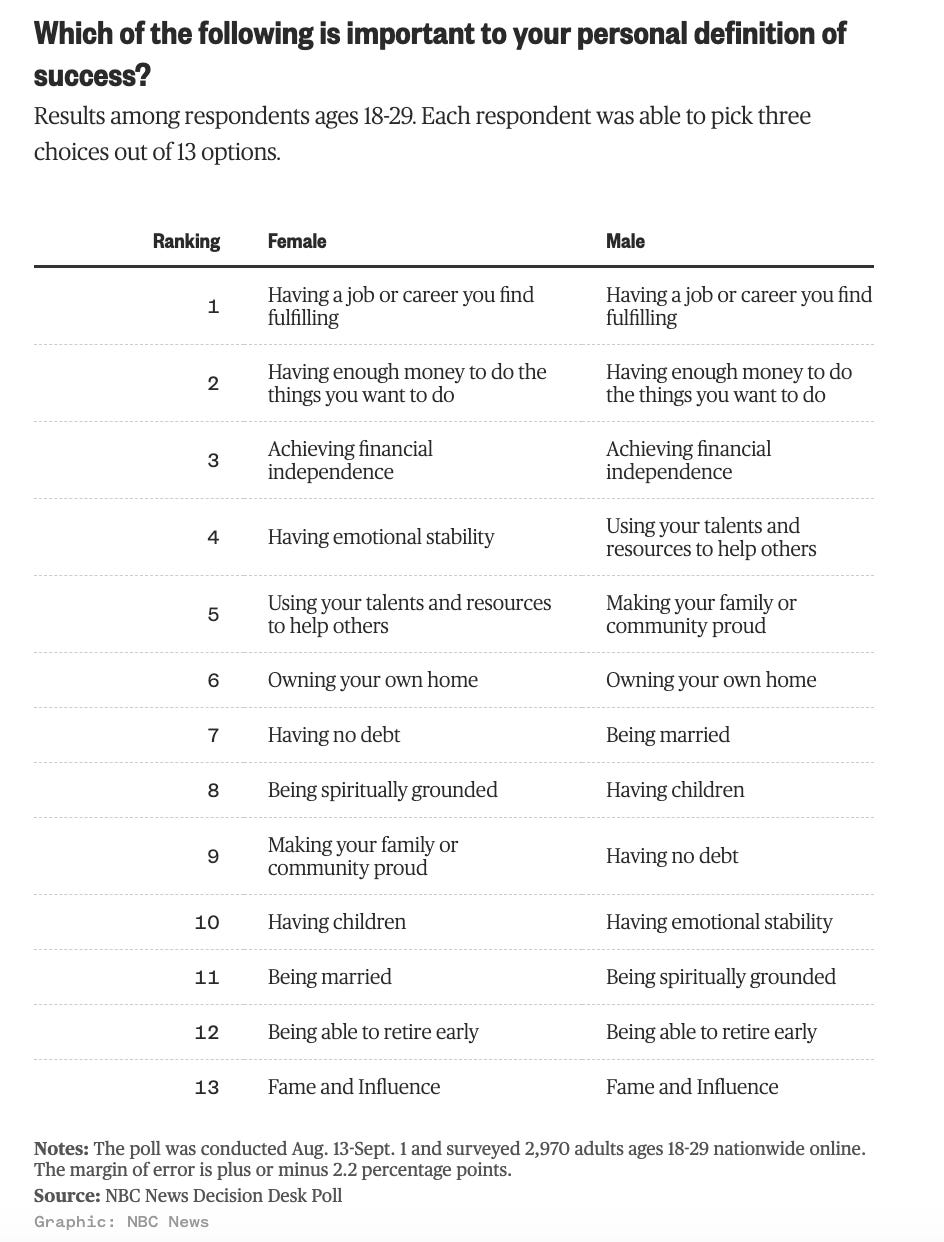

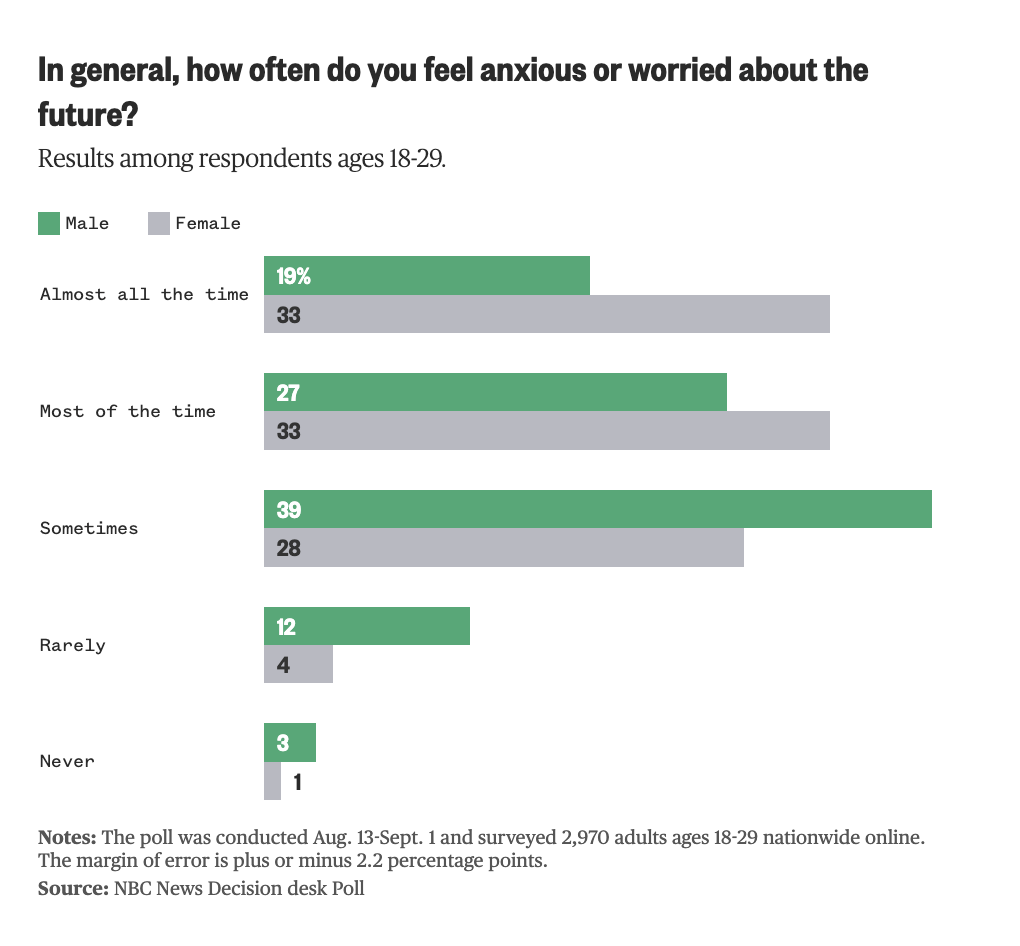

Before Kirk’s death, I’d been circling around some conversations online about what the future of relationships for men and women might be along a political spectrum. An NBC Poll published earlier this week that the political division among young men and women has worsened further. This divide doesn’t merely cover policy issues like trade or border security, but the very values by which we organize our lives. While young men and women alike seem to agree that money is a top priority, there is a deep disparity in the value given to having children or getting married. Male Trump voters under 29 ranked having children as number one in their personal definition of success, while female Harris voters ranked it second to last out of thirteen choices. There is a deep incompatibility at play.

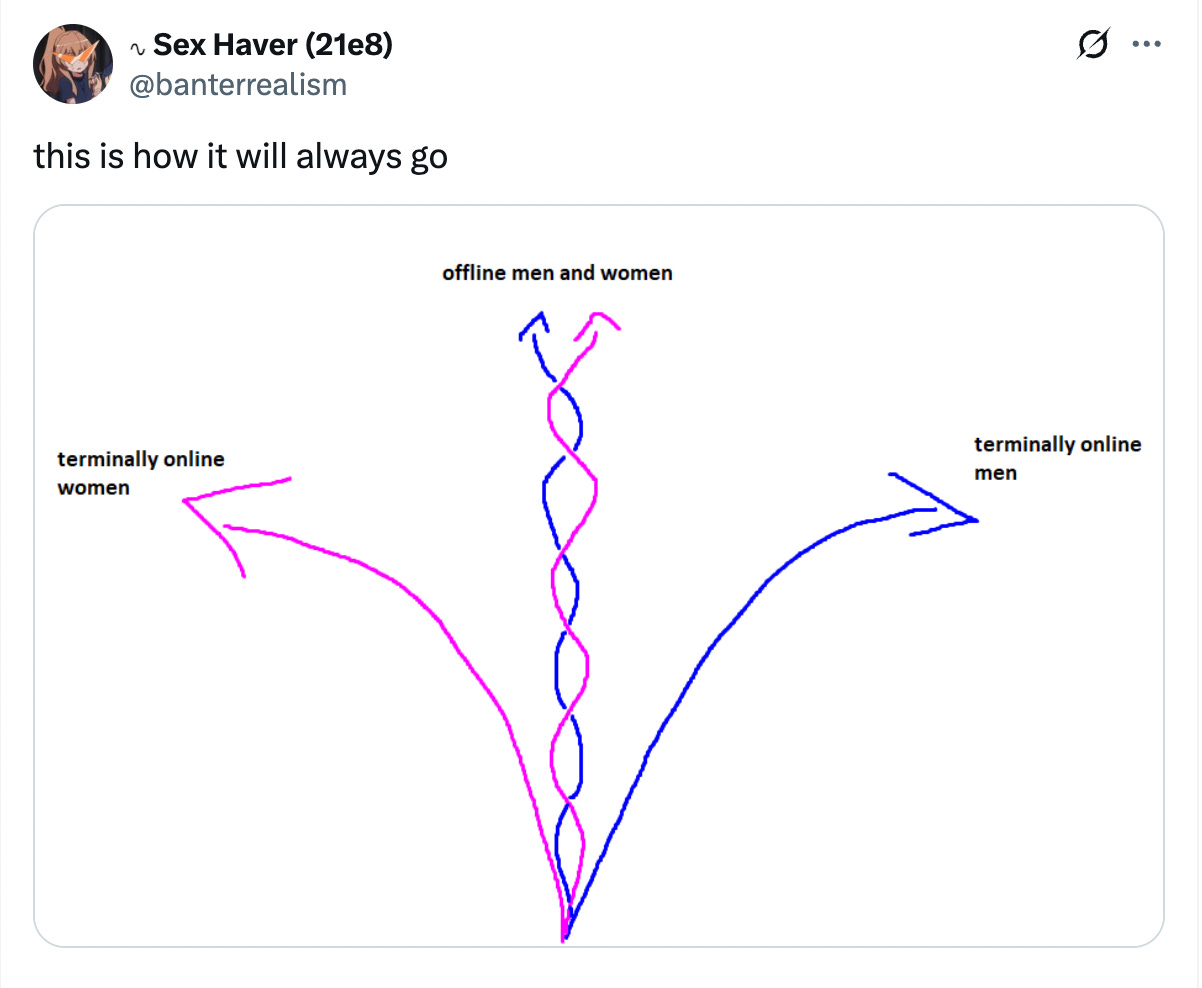

Some suspect that it is women who will undergo a corrective, first becoming more moderate and eventually taking on a perspective more aligned with the conservative beliefs of young men. Others, the opposite. Some (myself included) that a meeting in the middle is the ideal horizon. Within this conversation online, though, there was specific focus given to the state of “terminally online” men and women. The belief there is that terminally online women will continue to head left, terminally online men will continue to the right, and the men and women who have chosen to be offline will find harmony.

Of course, there’s some optimism there. It’s in line with many of other things I've said as a writer, encouraging people to get offline, whatever that means. However, I think we must nevertheless address what it means to be “terminally online” today.

In the past, it meant something like engaging heavily with 4Chan or being a moderator of niche subreddits. Maybe it meant you devoted most of your time to online video games. The point was that there was something fringe about it, some sort of specific and uncommon knowledge gained by thousands of hours spent online that made engaging in mainstream conversations a challenge.

That is no longer the case. There are few distinct differences between a “terminally online” young person and what we’d consider the “average” young person. If you are a young woman with a TikTok account used on a daily basis, even if you don’t post from it, you are likely to be “terminally online.”

Beyond the death of our attention spans and the wasting of our time, the consequence of this terminally online-ness is that it constantly exposes us to a set of beliefs that do not make us any happier.

Charlie Kirk death is itself an example of this — of how fringe beliefs, both on the left and the right, have become mainstream and hit this boiling point. There are endless lenses through which this could be dissected, but my current focus is one: How does this impact men and women and our ability to relate to each other and to find love and happiness?

The fringe beliefs at play are situated within the Gender War, and delivered through a mainstream method of exposure. That young woman on TikTok need only swipe a few times before finding a video encouraging her to give up on dating and sex, encouraging her to that you to believe that all men are misogynistic. You're constantly being exposed to horror stories about men, and with it, an attitude of suspicion is bred.

If we look at the end point of that particular area of ideology and its goals, we’re not finding women striving to form separatist communes of care and support exclusive from men. We’re not finding solutions or alternatives or much in the way of a lived community. Instead we only find the encouragement to be more online, to be more isolated, to be separate not merely from bad men but from each other. The same tech system of radicalization that has incentivized division along political lines is pushing division along gendered ones.

And how does that actually make a woman happier or more liberated? It itself is a new form of restriction, of confinement, of oppression. But when we look toward the other end of the Gender War, we see the same. The goal is not to push men to a better state of happiness, to liberate them from the various forms of oppression that men experience, be it class based or whatever else. It is to further isolate and restrict in order to keep you engaged with an algorithm. And of course, it all becomes a self-feeding cycle: of course women don’t want to date men who increasingly seem to hate them! And vice versa!

And so I have to question, is this all really a “last chopper out of Nam” moment? Were those of us who are in happy, loving relationships the last ones out? Again, I'm an optimist. I don’t want to think so. Maybe we all do just have to get offline, but this week has demonstrated that there is a lived, offline component to this political moment. The consequences are real, and they're material, and they’re affecting our day to day lives, online or off.

It is still, nevertheless, my fundamental belief that our capacity to relate to each other as men and women has not diminished beyond return. I am concerned about what this particular moment for us means and what has yet to come. Maybe the NBC poll of next year will look even worse. The phrase itself is suggestive of hostility, destruction and warfare — things many seem to be calling for in the wake of Kirk’s death. But what remains is the fact that letting this gender and political hostility shape our pursuit of love and connection remains a choice. Engaging with this digital corrosion remains a choice. The Gender War wants you to think you’re being drafted. You do not have to serve this.

i honestly think the tech barons have a lot to answer for. and i remember Scott Galloway saying that we're going to look back on this time decades from now and ask ourselves how we let them get away with all of this.

We’re going to have to reboot!! Start teaching people how to think for themselves again. Yes, GET OFFLINE! Get in TOUCH, (actually FEEL) the real world again. ♥️